Let Them Tinker

As a teacher, one of my favorite lessons went something like this:

Me: “Here’s a bunch of stuff. Use it to make the light bulb turn on.”

Then, with the exception of encouraging words, my part was pretty much over.

My fourth-graders would work in groups, usually for about an hour, testing different configurations of wires, batteries, and light bulbs. They learned to collaborate, to reflect on what did and didn’t work in failed attempts, to think logically about how energy might be transferred, and to persevere through frustration. In the end, all the kids always got it.

A lot of teachers are afraid of lessons like this one. I definitely was – in essence, I was completely out of control. I just sat back and watched my students build their own scaffolding. The first time I taught it, I’m pretty sure I only did because it was a part of my FOSS curriculum and I was too new to teaching to be afraid.

After I saw the results, though, I started looking for other ways to emulate this “these are your materials, this is your goal, go” model in all my subjects.

I haven’t taught fourth grade in two years, but I started thinking about this lesson again a few weeks ago, when I ran across a blog post by David Warlick that mentioned tinkering – the simple of act of messing around with parts to see what you can build. Not long after, I read an Education Week article entitled “Teaching Girls to Tinker.” The article examined the disconnect between girls outpacing their male counterparts in STEM subjects throughout K-12 schools, yet receiving less that a quarter of bachelor’s degrees in engineering and computer science. One of the article’s arguments is that, unlike boys, school-age girls aren’t encouraged to tinker, to build, or to fix things with their hands. Because of this, they’re severely lacking in the thinking and hands-on skills required in engineering and computer science professions.

All this got me thinking: I’ve heard dozens of stories about the world’s best inventors and engineers, as children, taking apart and re-assembling toasters, remote controls, and old computers at home. This tinkering time can teach kids tremendous lessons about problem-solving and logic.

But, these days, how many of our students, especially those in low-income areas, are given the time and tools to tinker?

Tinkering in Schools

If the skills are so essential, why not incorporate tinkering into school? I know what you’re thinking. “Well, Katy, that’s fairly obvious – with high-stakes testing, state standards, improvement plans, limited classroom time, and so on, teachers need to structure their teaching to reach specific, content-based goals. My administrators certainly aren’t going to give up any class time to let kids play with some old laptops.”

If the skills are so essential, why not incorporate tinkering into school? I know what you’re thinking. “Well, Katy, that’s fairly obvious – with high-stakes testing, state standards, improvement plans, limited classroom time, and so on, teachers need to structure their teaching to reach specific, content-based goals. My administrators certainly aren’t going to give up any class time to let kids play with some old laptops.”

Still, the long-term benefits of tinkering time are remarkable. In fact, in many ways, tinkering resembles inquiry-based learning, cooperative learning, and project-based learning, all of which have been proven to have long-term positive effects on student achievement and success. Plus, tinkering is friggin’ fun.

So what’s the solution? Most schools have elective time built into their schedules, as well as after-school interest-based clubs. If teachers are willing to give up a little of their time, I’m sure a tinkering class or club could be integrated into any school’s schedule.

Leading a Tinkering Club

Starting a tinkering club and leading a tinkering club are two very different animals. How, exactly, is one supposed to organize a club where students walk in and just mess around?

The Tinkering School might be a good place to start. Several years ago, Gever Tulley started the summer program to encourage creativity, collaboration, and problem-solving in students ages 8-17. Below, Mr. Tulley describes his school during a 2009 TED Talk:

Last year, I tried to start a robotics club at my school but, with a price tag of about $3,000, it proved to be cost-prohibitive. A tinkering club, on the other hand, could be started for FREE. Some schools with tinkering classes have a room where teachers and community members drop off old or broken electronics and other supplies. These parts are then recycled into innumerable objects by tinkering students. (Added bonus: those materials aren’t heading to the local landfill.)

As a club leader, you could make some ground rules (i.e., students are expected to always be working, not just socializing; safety goggles are a must), and then allow students to design their own projects. I think it’s a really good idea to have students work in groups, but that might be a flexible aspect of your club.

If students (or you) need a little more guidance, perhaps you could post a list of suggested outcomes – “build a bug that moves on its own,” “create a bridge that can hold 100 pounds,” etc. – and have students independently choose which project they’d like to complete.

With a limited budget, you could even have students work on projects for the good of the school, like creating inexpensive interactive whiteboards.

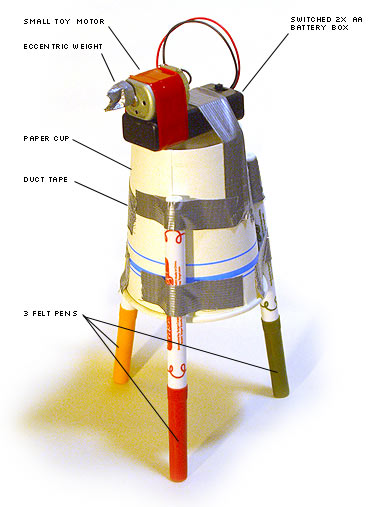

Another fun, inexpensive project (that, by coincidence, I just completed this weekend) involves building bristlebots, like this:

You could show tinkering students a simple bristlebot and assign them to improve it, in any way they’d like. Who knows? They may come up with something like this:

or this:

A tinkering club doesn’t only have to be about electronics, though. I used to teach a science lesson where students were tasked with using water to lift a weight one foot vertically. Most of the kids used various materials to build a slide with a water wheel at the base. As water flowed down the slide, it would turn the wheel – there were no motors, wires, or batteries involved.

For more tinkering project ideas, check out Make, Evil Mad Scientist Laboratories, and Junkyard Wars for the Classroom. (The Junkyard Wars site even has lesson building tools, including checklists, certificates, and rubrics.)

Lesson Integration Ideas

Disclaimer: It’s difficult to offer lesson integration ideas for tinkering because, in its most pure form, tinkering is completely student-driven. Students mess around with what they find and decide what they’d like to build. However, there are some times when guided activities might be preferred in a tinkering class. Perhaps some of your students seriously struggle without guidance. Maybe, early on, you’d like to use a guided lesson to model club expectations before students are allowed to venture off on their own. And there’s always the opportunity for a year-end tinkering challenge. So I offer a few possible guided tinkering ideas below, but I also urge anyone undertaking a tinkering club not to overplan — as much as possible, give tinkering control over to your kids.

Elementary Classrooms

Grade: K-3

Subject: Technology (tinkering)

Objective: The student will be able to create an object to solve a problem or answer a question.

Given time and materials, it’s amazing what younger students will build. Work with students on safely using tools like wood and wood glue. If you feel comfortable, allow older kids to use hammers and nails. Then set them loose in a room full of recycled, donated supplies.

Guide students with an objective, like “build a toy you’d like to play with” or “build something for our school garden.” But be sure their goal has a real-world connection. When young students see that they can build something that will be used, their motivation and self-esteem goes through the roof.

As problems arise, it’s a great opportunity to teach problem-solving skills. For example, maybe a student will build a bird feeder and then notice that squirrels are stealing all the food. How can the design be improved to keep the squirrels out but let the birds in?

Middle School Classrooms

Grade: 4-8

Subject: Technology (tinkering)

Objective: The student will be able to create an object to solve a problem or answer a question.

Once students have a strong grasp on circuits and how they work, thousands of tinkering opportunities open up. Students can use motors, switches, and batteries to create complex robots and machines.

Have your students discuss school-wide problems they think they can resolve. For example, maybe they’ll notice that the window where they turn in their lunch trays is always backed up and piled high with dirty lunch trays. Then, have students work independently or in groups to design and build something to solve this problem. Maybe they’ll create something good enough to solve the problem. Maybe they won’t. Either way, the objective has been acheived — in tinkering, it’s process over product.

High School Classrooms

Grade: 9-12

Subject: Technology (tinkering)

Objective: The student will be able to create an object to solve a problem or answer a question.

Host your own Junkyard Wars competition, using a room of donated “trash” as your school junkyard. Give students a problem they’re challenged with solving, such as building an underwater robot that can lift an object from the bottom of a pool. Then, have kids compete to create something (using only what’s in the “junkyard”) that can complete the challenge in the fastest time.

Over spring break I spent a couple of hours cleaning out my basement. I found an old computer that I had been saving for spare parts. I decided I didn’t need it and put it near the trash. Then curiosity got the better of me and I started to tear it apart. I pulled out the processor (PIII), ripped out the mother board and mounted the whole thing on the wall by my workbench. I’m an adult and still enjoy tinkering! I hope others will be encouraged to allow more tinkering in the classroom.

@John Sowash, That’s so cool! I just recently re-discovered my love of tinkering as I started playing with Wiimote whiteboards and fixing old computers to update them with Ubuntu. Taking about 5 minutes to build a bristlebot, though, got a ton of attention from friends — now, they all want to build one.